Rewriting The Courage to be Disliked

I read The Courage to be Disliked 7+ times in four years. While the book has excellent philosophy, it lacks clear explanations and practical guidance. Here’s how it could be improved.

Part I: Evaluating the core claims of the book

Part II: How I’d rewrite it to be more effective

Part I: Evaluating the core claims

Claim #1: Emotional “issues” often have hidden functions

The most important mindset presented in the book is Teleology: the study of the purpose of a given phenomenon, rather than its cause.

For example, the book would claim that someone who is depressed is in that state not because of childhood trauma, but because depression helps them avoid situations that currently feel unsafe. This mindset is contrasted with the more common “etiology”, which blames today’s problems on past injuries, leaving little room for future growth.

Put another way:

Teleology is quite contrarian to our usual way of making sense of the mind. It’s also extremely valuable. Without it, I wouldn’t have been able to resolve my own issues or help others with theirs. Despite this value, people really, really, really don’t get teleology. Teleology is essentially antimemetic in our culture.1 Understanding teleology is one of the best reasons to read TCTBD, in my opinion.

But. The book’s explanation is awful. The part that attempts to explain it is literally titled “Trauma Does Not Exist.” This frame needlessly triggers many of the people who could benefit most from it, preventing them from engaging. A clear example is this /r/CPTSD thread: “Do not read the book "The Courage to be Disliked". It contains terrible advice for trauma survivors”. Because the book’s wording is poor and practical advice is lacking, the redditors missed the extreme value of the teleology frame.

In Part II, I’ll discuss how to explain teleology better.

Claim #2: “All problems are interpersonal relationship problems”

I’m unable to steelman why the book says “ALL” problems are interpersonal, but I’ve come to agree that many, maybe even most, human problems relate to social interaction. This gets at the second most important point in the book:

You were so afraid of interpersonal relationships that you came to dislike yourself. You’ve avoided interpersonal relationships by disliking yourself.

This is extremely true. I completely agree.

In the vast majority of cases I’ve seen, the way that people stop disliking themselves is by feeling safe in their interpersonal relationships. When someone dislikes themself, they stoop or take up less space, make fewer requests of others, take fewer social risks, and so on. These all have the effect of minimizing interpersonal conflict and minimizing dislike.

People generally don’t stop disliking themselves until they’re ready to be disliked by others. Disliking oneself often appears strategic.

Teleology strikes again!

Claim #3: Whether you outgrow your issues is your choice

From the book:

Whether you go on choosing the lifestyle you've had up till now, or you choose a new lifestyle altogether, it's entirely up to you.

✅ Growth follows from the belief in growth.2 Growth is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The inverse is also true: if you believe you can’t grow, you probably won’t. Many people have this. “Learned helplessness,” it’s called. The book’s advice for these people is basically “you gotta choose to grow,” which is odd because… learned helplessness is often serving a function!

Many people feel like outgrowing their issues is a subtly bad thing. Strangely, the book doesn’t apply the mindset of teleology to the absence of someone’s willingness to grow.

Claim #4: You are autonomous, and so are other adults (Separation of tasks)

The book introduces a concept called “Separation of tasks” to show what healthy interpersonal interaction looks like. However, the description of how to separate tasks is so muddled that I entirely missed it the first four times I read the book. It’s just this line: “Think, Who ultimately is going to receive the result brought about by the choice that is made?” This explanation is difficult to apply to real messy relationships, especially when strong emotions are involved.

Here’s how I would explain the underlying concept instead:

You can’t fully control how other people feel or behave. You can’t fully read others’ minds. Other people can’t fully control how you feel or act. Other people can’t fully read your mind.

Every adult is autonomous: you can only control your own behavior and read your own mind. (For a rigorous explanation of this idea see my posts on Markov blankets and causal distance.) These limits reveal that there are natural boundaries that separate where my “tasks” end and yours begin.

Most interpersonal conflicts involve a failure to acknowledge these natural boundaries: trying to force others to feel differently, presuming we know others’ mental state, expecting others to fix our feelings, or hoping others will read our minds. Meanwhile, healthy interactions are characterised by not trying to do any of these things.

It’s certainly nuanced. I’ve spoken to dozens if not hundreds of people who disagreed with it at first.3 But overall I think it’s a great point.

Claim #5: Separating tasks will improve your relationships

The book claims separating tasks “is enough to change one’s interpersonal relationships dramatically.” I actually think this is both very wrong and misleading as it reverses causality.

Like, yes, healthy interaction involves separating tasks. But that does not mean that you can just consciously choose to separate tasks.

I know that because I spent six months trying to teach others how to. I believed that if someone could understand separation of tasks, then they’d be able to separate them and stop having so many unnecessary interpersonal conflicts.

Completely wrong. I tried to teach a bunch of smart friends, and they would like the idea, explain it back well, etc., but every time they got into a real conflict, their understanding of how to separate tasks completely fell apart. Huh?

Imagine there was only one person in the world who could give you food. Wouldn’t you do everything you could to prevent them from disliking you, try to read their mind, etc.? Wouldn’t you completely fail at separating tasks?

When you feel like other people have things you can’t go without, then you have extremely strong incentives to manipulate them. Your intellectual understanding of “separation of tasks” is powerless against strong feelings of insecurity.

Once I noticed this, I stopped trying to teach others how to separate tasks. Instead, I helped people unlearn. This worked: they began to separate tasks automatically, without me explaining! (Case study.4) The result is even cooler than what the book says: when you feel secure, separating tasks is effortless.

tl;dr: If you don’t already separate tasks naturally, you probably can’t just choose to start separating tasks.

Claim #6: People need to feel like part of a greater whole

The book calls this idea community feeling: humans thrive when they believe “my effortless existence benefits the group.” (Your group/community could be people, animals, or even the cosmos.)

Crucially, you can’t ever really know whether you’re actually benefiting others — maybe everyone is lying to you, maybe the person you’re helping is actually baby Hitler, etc. — instead you just have to have faith in your own intentions to do good and help others. Having that faith is a choice.

I like this part of the book; I have no additional suggestions. I wrote more about it here.

Claim #7: You can choose to be present

if one is shining a bright spotlight on here and now, one cannot see the past or the future anymore.

Do not treat [life] as a line. Think of life as a series of dots. If you look through a magnifying glass at a solid line drawn with chalk, you will discover that what you thought was a line is actually a series of small dots.

Imo the book makes the same mistake it did with separation of tasks: suggesting that you can choose to be present, when in reality you probably can’t. I haven’t seen this advice work except through extreme brute force (e.g., long meditation retreats) or luck.

I spent 5 months “trying to be present” on my own but kept dissociating and wasted months of suffering, so I have personal disdain for this.

My model now is that presence is natural, but gets blocked by insecurities. Simple teleology: if you have difficulty being present, there’s probably hidden functions! The resolution is not through further conscious mindset or choice, but through unlearning.

Now, with that out of the way…

Part II: How I’d rewrite The Courage to be Disliked

Improvement #1: A less triggering explanation of teleology

Firstly—don’t say “Trauma doesn’t exist”. Instead, focus on what does exist5: emotional issues with hidden functions. This shift in perspective will also fix the issue of unnecessarily triggering people who feel strongly about trauma.

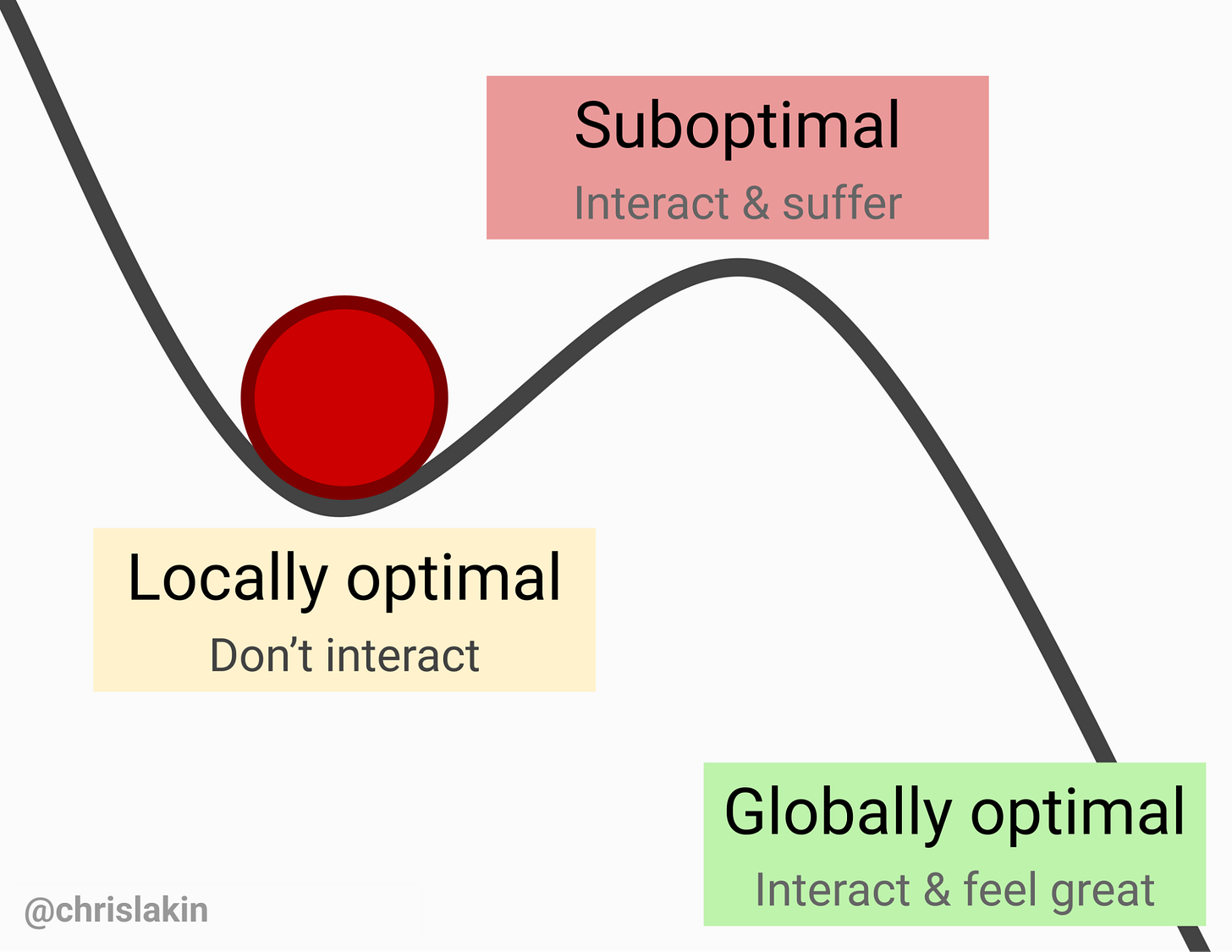

It’s also possible to explain teleology faster and more intuitively. For example, I’ve found it helpful to drop the term “teleology” entirely and rebrand as “locally optimal” instead.6 For example, back in 2022 when I was withdrawing from life, the suffering incentive landscape seemed to be:

More here. Next, I would mention how teleology is actually integrated into one’s life.

Improvement #2: Stop “self-help”

Imo, the most harmful idea in The Courage to be Disliked is the idea that you can help yourself. That, “If only I think hard enough about how my own behavior might be teleological, then I’ll figure everything out and grow.”

I’ve spoken to dozens of people about this book, and not one has remarked: “I read The Couraged to be Disliked a long time ago. I applied it correctly. I’m doing a lot better now.”

In fact, most people I know who read TCTBD misunderstood it!

For every one person I’ve seen maybe succeed at “self-help”, solo I’ve seen more than 10+ waste multiple years of their life flailing making little to no progress.

Improvement #3: Present better skill trees

In general, personal growth has a skill tree: you must progress in a valid order. But some of the advice in this book implies that you should work on Level N skills (separating tasks, being present) before you have Level N-1 skills (having the courage to be disliked, feeling secure about stuff) — ???

If I rewrote the book, I’d flesh out a better skill tree for how to follow advice for different stages of the path.

Improvement #4: Validate the rewrite on real people

There’s a reason why I had to read The Courage to be Disliked 7+ times (and its sequel The Courage to be Happy 3+ times) over four years: I had to do most of the thinking on my own time!

Everything in this post makes me wonder… Did the authors not test their book? As in: give the draft to representative people with issues the book aims to address, have the people read it, interview them to see if they correctly understand it, and follow up a few months later to see if those issues improved.

I would guess they didn’t! (Do you know anyone who deeply applied the philosophy because of reading about it in this book? I don’t!) This is crazy to me.

If I rewrote The Courage to be Disliked, I would test the new instructions to see if they have their intended effect on readers.

Conclusion

While I dislike much of the literal wording in The Courage to be Disliked, I deeply agree with its underlying philosophy. A steelman of its claims reveals many ideas that are both very wise and very unusual. I hope someone writes this steelman because it could help a lot of people.

If you have questions about the contents of the book, you can copy the full text into AI for discussion.

About | Twitter

In the past, when I tried to explain to others, “Emotional issues are often useful right now in the present”, they often replied, “Oh so it was useful at some point in the past but it’s not useful anymore?” And I’d say, “No, useful RIGHT NOW.” Finally, they say, “Oh, because evolution created this behavior but it doesn’t help in the modern environment!” ……… Fortunately this stopped when I found the “locally optimal” framing.

In the past three years I’ve spoken to dozens if not hundreds of people who find this concept objectionable. After spending hundreds of hours thinking about it and running two adjacent AI safety and category theory workshops, I remain confident. Most objections appear to be driven by emotional insecurity that can be unlearned.

Case study interview: Man became more secure and automatically started separating tasks. Effects 18+ months later.

By focusing on what doesn’t exist, the book is also failing the “don’t think about elephants” test.

Also why this blog was named Locally Optimal.

This is such a great post, especially in acknowledging the limitations of unnecessarily hostile framings. The LessWrong links were also illuminating; lovely work

Awesome post. This is such a strange book, deep insights and good ideas encased in such a thick, opaque shell, that you either bounce off of it and become a vocal hater, or are so desperate to steelman and understand its ideas that you actually crack through to the diamond at the center, only to find that 1. precious few others are willing to do all that work, and 2. the diamond is far from practical, its mostly glittery, but if you can fashion it into a tool it is pretty damn solid.