AI alignment inspired by human alignment

Update: new post that makes this more concrete:

Understanding human alignment ⇔ Understanding alignment ⇔ Understanding AI alignment

E.g.: Boundaries

Boundaries provide autonomy. When individuals’ boundaries are preserved, unnecessary conflict between those individuals is minimized. Boundaries could help specify the safety in AI safety. [Claim #4 here, Claim #9 here.]

My work in this area has mostly been writing distillations and convening researchers.

Conceptual Boundaries Workshop (3-days)

Mathematical Boundaries Workshop (5-days)

I became interested in this after I started thinking about the human boundaries, and this required understanding the causal distance between agents in general. And as it turned out, other researchers were already also thinking about this.1

How might boundaries be concretely applied to AI safety? One way is as a formal spec for provably safe AI in davidad’s £59m ARIA programme.

E.g.: “Goodness”?

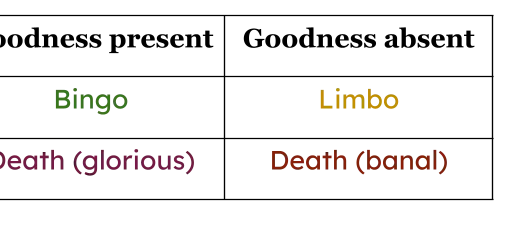

One way I like to think about what we want from ‘full alignment’ is two somewhat-independent properties:

(Also, notice that I haven’t smooshed Goodness and Safety into one axis. Usually when people do this they call it “Utility”.) Goodness and Safety are have different causes!)

And while boundaries/safety is nice, they don’t actively provide Goodness. So the question is: How can Goodness be specified?

Similarly, for human alignment: learning to do boundaries minimizes unnecessary social conflict (personal experience), but… What causes joy? Connection? Collaboration? What causes Goodness?

I suspect the answer is whatever causes collective intelligence / synchronous social interaction.

Why might AI alignment be like human alignment?

As Michael Levin says, “all intelligence is collective intelligence”. Every intelligence worth hoping for or worrying about is made of smaller parts.

In which case, alignment itself can be defined as “How do smaller parts build bigger agents and avoid internal cancers?” Human alignment deals with the same questions:

How do groups of humans make a decision?

How do parallel predictions in the mind decide what’s right?

Why the emphasis on psychology?

It has excellent feedback loops!

When the research is right, people quickly outgrow lifelong mental issues (eg).

More explained here:

Thanks to thinking partners Alex Zhu, Adam Goldstein, Ivan Vendrov, and David Spivak. Thanks to Stag Lynn for help editing.

Were the other researchers inspired by social boundaries too? E.g.: I haven’t directly asked Andrew Critch how much his thinking about boundaries for agents and for AI safety was inspired by his thinking about social boundaries, but it does seem likely.